National Ebola Training Academy Begins

Originally written February 23, 2015

We made it to Sierra Leone! It was touch and go for a minute in DC, where we sat on the tarmac for three hours while they plowed the runway and de-iced our plane. As we watched the time for our layover in Brussels trickle away, I started to get pretty nervous – flights into Sierra Leone only leave twice a week. Fortunately we landed in the nick of time, and the wonderful flight attendants made an announcement that there were some humanitarian workers trying to make a tight connection to West Africa, so everyone else kept their seats so that we could get off first!

Something like 30 hours after we left Boston, we finally landed in Sierra Leone on Sunday night. The same smells I know well from East Africa made me feel at home from the moment I stepped off the plane. Even after so many hours of travel and sleeplessness, I knew I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

The reality of the Ebola outbreak hit us as soon as we walked across the tarmac and reached the door to enter the airport. Chlorine hand washing stations awaited us outside, and everyone was made to scrub their hands before being allowed to enter. After reading so many news stories about it over the past several months, it was surreal to actually wash my hands with chlorine to prevent spreading Ebola for the first time.

These handwashing stations are at the entrances to most buildings to prevent the spread of Ebola.

Once inside the airport, it was legitimately the most fun I’ve ever had in customs. We were surrounded by other humanitarian responders from MSF (Doctors Without Borders), World Health Organization, Direct Relief, you name it. Any tourists have long since left Sierra Leone, but it was lovely to chat with other humanitarian workers as we waited.

After clearing customs, I waited in line to have my temperature checked with an infrared temporal thermometer (a handheld scanner that allows the user to check temperature without coming into contact with the patient). It’s an odd moment, if you let your imagination run away with you and start to wonder what might happen if your temperature comes out high… Fortunately, I was a normal 36.3 C and was waved right on.

A short bus ride, ferry trip, and another bus took us to the Partners in Health (PIH) guest house in Freetown, which is lovely. We were met with another handwashing station at the front door, and had our temperatures checked and recorded in a log, as we will every time we enter the building. Our apartment is quite fancy by developing country standards, with electricity by generator, running water (though not hot), and wifi that comes and goes. We even have a washing machine! My coworkers are laughing at me right now as I sit on the couch, blogging beneath a line of drying scrubs and underwear.

Our first day of World Health Organization training was today. It was clearly fascinating since I was able to stay awake for 8 hours of class despite some serious jet lag!

We PIH-ers are just about the only non-Sierra Leoneans there, which is lovely because we get to interact with national staff who have been fighting Ebola much longer than us and living the reality of this outbreak every day. Most of the Sierra Leoneans I’ve spoken with have been working in Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) for several months and are attending training for the third time. Since protocols change quickly as research and experience grows, they are encouraged to take the training again every few months. We of course all took advantage of the hand washing station before entering the building, and had our temperatures checked and recorded by the staff.

Washing my hands before entering training on Monday morning

Our first lecturer wished us all a good morning, and chided our lackluster response with, “That ‘good morning’ has Ebola!” I suppose you can’t do this work if you can’t find a way to laugh about it.

We were reminded of the huge importance of infection control and prevention among healthcare providers, not only to keep ourselves safe, but because of the role it plays in public perception here. We were told that, “You have not come here to die,” which is always reassuring!

At the beginning of the outbreak, hundreds of Sierra Leonean healthcare workers contracted Ebola due to poor infection control measures; 221 have died to date. To the public it seemed like the situation was hopeless: Why would you come to an Ebola Treatment Unit for care, when those who are caring for you are dying themselves? To put it simply, dying sends a bad message.

Fortunately this perception has shifted as infection control measures and patient care have improved, but we as healthcare workers play an important role in continuing that momentum. Ebola survivors are also pivotal in instilling hope and proving that admission to an ETU is not an automatic death sentence. Because they are immune to the virus for an unknown period of time, many survivors have also been helping to provide care in ETUs.

We see educational Ebola signs all over the city. This one reminds people that Ebola isn’t a death sentence, and encourages them to call the emergency Ebola number early if they’re ill.

It has quickly become clear that habits I live with in the US will need to be broken ASAP. One of our trainers stepped into class this morning to let us all know that they had been watching us for 15 minutes, and we each touched our faces an average of 3.4 times per minute. Considering Ebola enters the body through our mucous membranes (eyes, nose and mouth), I’ll just have to learn to put up with the itch on my nose.

We also don’t shake hands when we meet someone new; instead, we offer to touch elbows. It’s hard not to feel rude at first, but the stakes are too high to care really.

The basics are essential here: We all re-learned how to wash our hands today, the Ebola way. I’m certain I have never paid such close attention to a person washing his hands as I did at that moment. It takes a full minute, with maneuvers to make certain that we clean every centimeter of our hands. We practiced in a group, everyone nit-picking each other’s technique because it will likely be the thing that keeps us Ebola-free.

The hand washing technique we’ll use in the Ebola Treatment Unit

Next we tested our ability to remove dirty gloves without contaminating ourselves. After dipping our hands in mud, we each SLOWLY removed our gloves, careful not to snap them and fling infectious material, and making certain that no part of the outside of the glove touched our skin. Our trainers inspected our hands and declared, “Quarantine!” to anyone with a speck of mud on their skin. It’s excellent practice for when our gloves will be covered with bodily fluids, and it’s no longer a game.

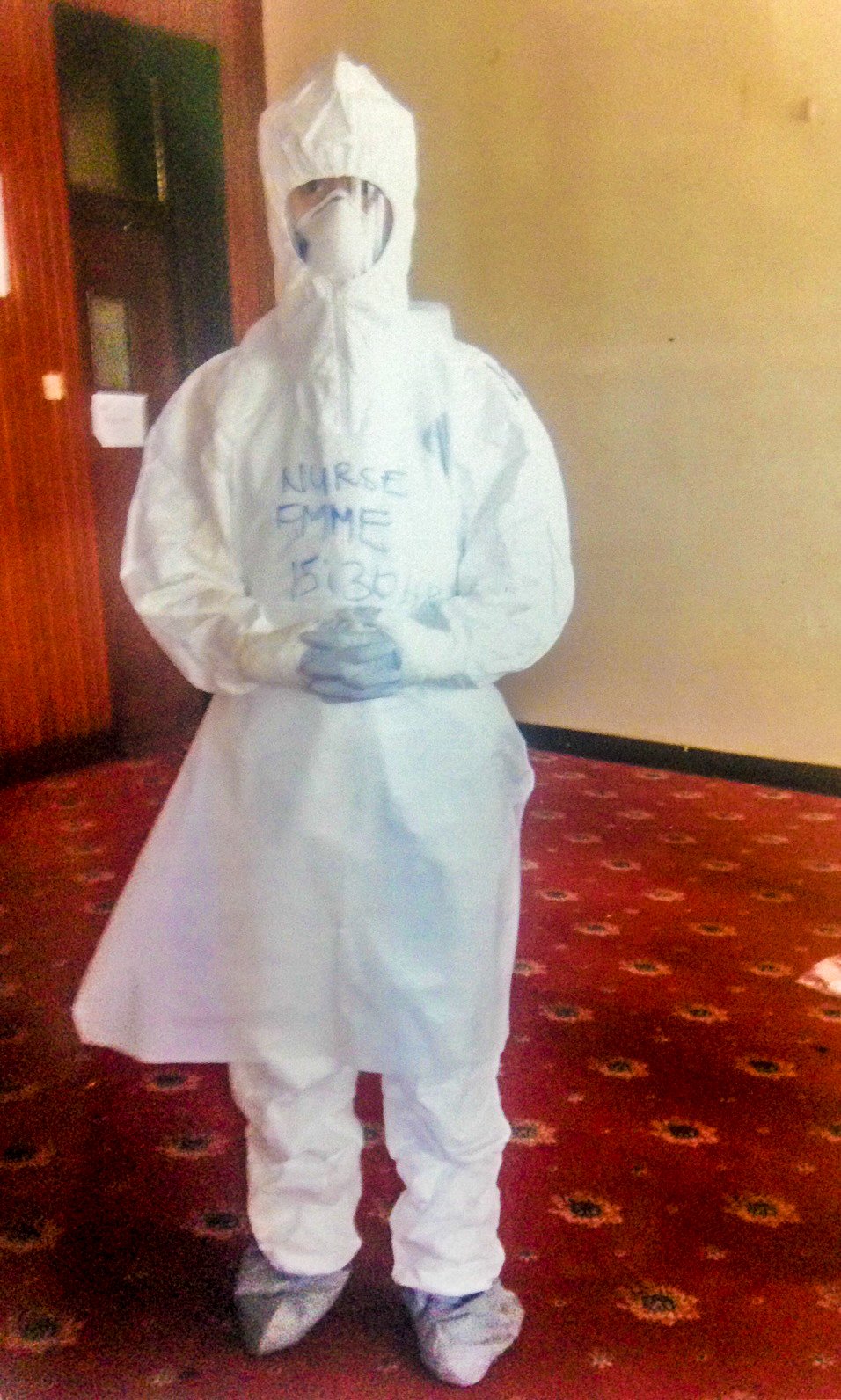

And finally, it was time for the infamous suits. We refer to them as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and we’ll need to know exactly how to don and doff them in order to keep ourselves safe in the red zone.

Yep, I’m in there somewhere!

Today was just a test run, with trainers walking us through the correct procedures for putting on each item – rubber boots, suit, first pair of gloves, hair cover, mask, face shield, hood, apron, and second pair of gloves. Another surreal moment: to be completely encased in the suits I’ve been seeing on TV for months.

Between the mask, face shield, and hood, my visibility was incredibly limited and I struggled to hear what the nurse next to me was saying. We then took a walking lap around the building, getting a feel for how we would react to the PPE. My lovely African teacher acted as my partner (everything in the red zone is done in pairs for safety), and kept asking me, “How are you doing, buddy?” every few minutes.

It’s hot in there, for sure, but I didn’t feel faint or claustrophobic. We’ll see in the coming days if that changes when it’s an hour and a half, rather than five minutes, that I have to work inside the suit.

The moment you remove your PPE is the highest risk time for contaminating yourself, so this skill is crucial.

My partner walked me through each step, as the support staff will do in the actual ETU. Our motto is “There is no emergency in Ebola,” meaning that we do everything at a snail’s pace to ensure we are doing it safely. We remove each part of the PPE carefully, with a minute-long hand wash in between each piece. It’s a long process. I’m actually looking forward to getting more practice tomorrow; I’d like it to be muscle memory by the time I’m doing it in real life.

We wrapped up the day with a temperature check, the staff scurrying around to make sure no one left without recording theirs in the log. After a delicious dinner of rice, fish and plantains, I’m now off to bed to get a handle on this jet lag before more training tomorrow.

By the way, a PIH staffer told me that they get more volunteer clinicians from Washington state than anywhere else. So way to go, fellow Washingtonians!

Next post: Stairway Troll

Previous post: I’m off to Fight Ebola

You Might Also Like:

This post contains affiliate links. This means that if you decide to make a purchase through any of the links we recommend, we get a small commission at absolutely no cost to you. This helps with the cost of keeping this site running – so thank you in advance for clicking through! And not to worry, we don’t recommend anything we don’t fully believe in or that doesn’t align with our values.