ETHICAL SOCIAL MEDIA GUIDE: TIPS FOR RESPONSIBLE TRAVELERS

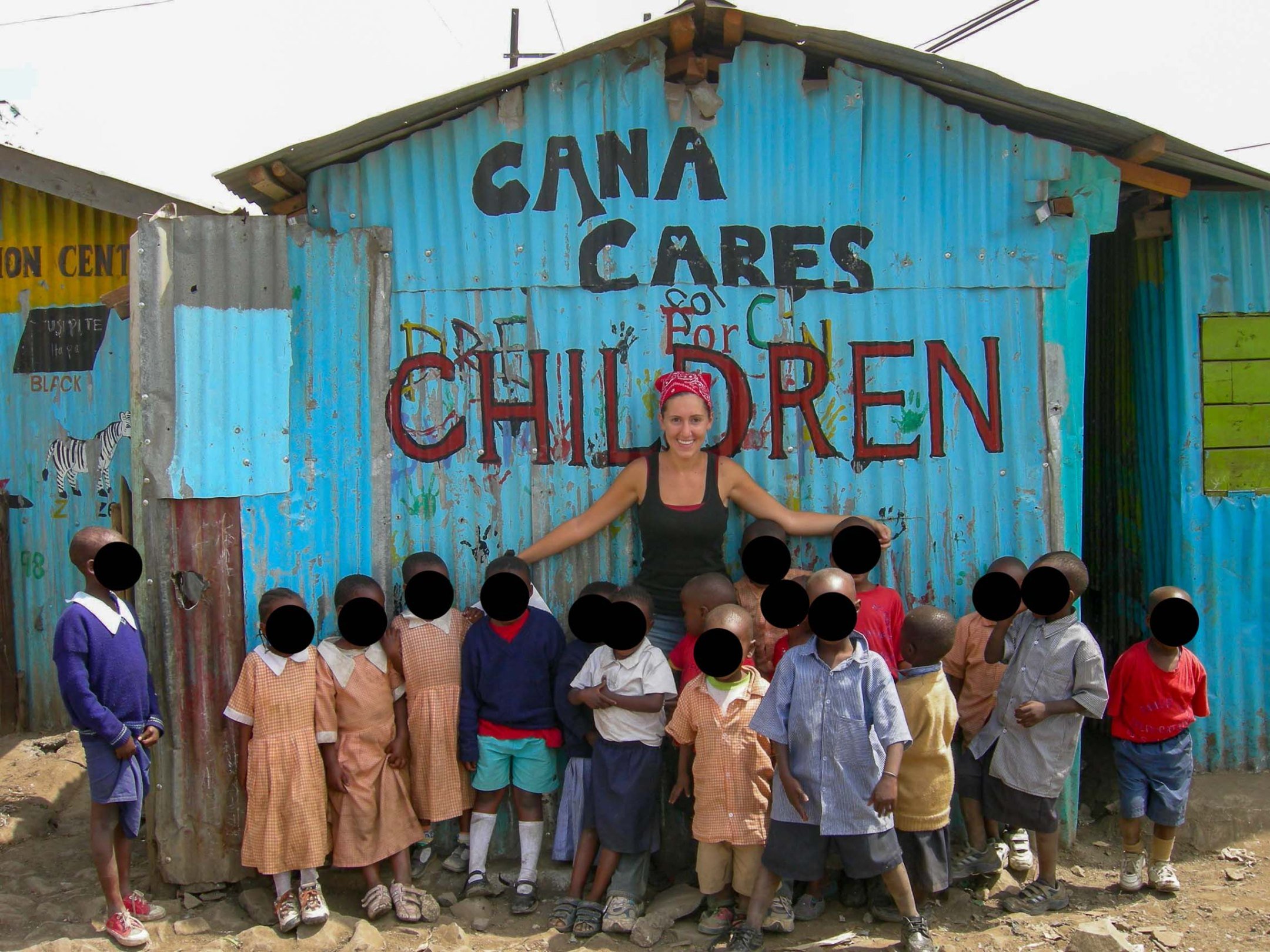

Before I knew better: Not only did I not have informed consent from these kids to share this picture, but now I cringe at the story this photo tells. It makes me look (incorrectly) like a hero, and promotes the stereotype of “poor but happy” African children.

When I first started traveling and volunteering abroad, I knew nothing about ethical social media use. The issue never even crossed my mind. I just dumped my photos onto Facebook and waited for the likes to roll in.

Flipping through old photo albums the other night, I found pictures that would make me cringe and search frantically for the “delete” button if I saw them on my feed today. Here I am cuddling a young Belizean girl I don’t even know; here I’m posing by the bedside of a Tanzanian woman who’s just delivered her baby; there’s the profile picture I was so proud of, where I’m benevolently wrapping my arms around a group of Kenyan orphans (facepalm).

Nowadays, folks are beginning to know better. Disrespectful photos with harmful captions get called out on social media; images go viral. But a few years ago, that could easily have been us earning our 15 minutes of infamy by sharing a photo without considering the message it sent. So how do we know what photos to take and post, what captions to write? What’s OK and what crosses the line?

Ethical Social Media 101

My #1 rule for sharing photos on social media is:

FLIP THE SCRIPT.

Turn the scenario around and imagine that you’re the subject of the photo, and a tourist you don’t know is taking it. Would you want a photo like this of yourself posted on social media?

It seems like everyone, myself included, suddenly becomes a documentary photographer the moment we set foot in a new destination. We’re so excited to capture all the fascinating people and places we’re seeing, that we don’t stop to think if we should.

For example: The first time I volunteered in Kenya’s sprawling, impoverished neighborhood of Kibera, I was so blown away by the poverty that I snapped dozens of photos and dumped them all right onto Facebook, thinking I was “raising awareness”. But would I want a similar photo taken of myself? Absolutely not.

If a tour group rolled up to my home in Seattle and started snapping photos of me just living my life (“Look at the American watching TV! Her hair is such a mess, and wow she’s really going to town on those Cheezits!…”) I would be mortified.

Scroll through #kiberaslums on Instagram and you’ll see a lot of photos like this. But would we want photos of ourselves and our homes displayed on social media to garner pity and promote “awareness”?

So nowadays before I snap a photo, I think to myself: If I was this person, would I want this photo taken? If the answer is no – because the photo makes them look bad, or it’s too personal, or for whatever reason it would make you feel uncomfortable – then put the camera away.

Another way to look at flipping the script is: Would you take the same photo at home in your own country?

If I was walking down the street at home in the USA and saw a random cute kid, would I whip out my phone and take a photo of them? Absolutely not – because that would be creepy.

So what makes visitors to developing countries feel like it’s appropriate to snap pictures of strangers’ kids? (Check out this article for proof that tourists don’t pull this stuff in Europe.)

I remember taking a photo of this child in Nairobi because I thought it was funny that he was wearing a Christmas sweater and knit cap in 80-degree heat in July. Would I have done the same in the US? No way.

Another frighteningly common example of this occurs among international volunteers. We’re so eager to share what we’re up to with family and friends that we photograph things we’d never dream of capturing at home.

I’m guilty of it myself: I work as a nurse in the US, where I would absolutely be fired if I shared photos of my patients on social media. But somehow when volunteering abroad, I used to think that rule no longer applied – I have photos of women in labor, patients getting stitches, babies dying of jaundice, you name it.

Now I know better – and before I take any photos in a healthcare situation I ask myself: Would I snap this same photo if I was at work in the US?

For anyone volunteering to teach school abroad, the same situation applies! I visit my husband’s primary school class at home all the time, but I’ve never posted a photo of his students because I inherently understand that doing so would put him in hot water. But I’d bet my travel budget that everyone reading this article has seen photos of beaming white volunteers surrounded by their African students.

Why are volunteers praised for sharing those photos, when they’d never post the equivalent at home? Are kids in developing countries less worthy of privacy?

Which brings us to the issue of consent.

GET INFORMED CONSENT.

Now I can almost hear people arguing, “But those kids wanted me to take their picture! They all ran up and asked me to!”

I’m sure that’s true. I’ve had the same experience countless times all over the world. The moment you pull out your camera, a throng of adorable children descends upon you, begging to have their photo taken and then asking you to flip the screen around so they can see it.

The question here is: Does that really count as consent? Do you think these kids have any real understanding of Instagram and Facebook, or the startling number of people who might see this photo once it’s online? Do you sit down and say to them: I have 10,000 followers on Instagram, do you mind if I let them all see your face?

Or is it more likely that these kids are excited because they don’t have access to digital cameras and iPhones, and maybe they don’t get to see themselves in photos very often (or at all)? They’re not thinking, “I want all her followers to see how cute I am!”, they’re thinking, “Cool! A camera!”

Here’s where you have to be the adult and decide what’s ethical social media use. If there’s no parent around from whom you can gain meaningful consent, those photos do not belong in your feed. Children may not understand the ramifications of having their image splashed across social media, and even if they did they may be so eager to please you (their new friend with the fancy toys) that they would never consider telling you “No”.

And let’s be clear: You need consent from adults, too. None of this taking a photo and posting it with the assumption that the subject will never see it anyway. Now more than ever, no matter what far-flung corner of the world you’re traveling in, people are likely to have access to social media. That picture you share of your host family in Cambodia that you think none of them will ever see? It’s just a matter of time before one of them looks you up on Facebook and finds themselves in your travel album.

So how exactly do you ask for consent?

A picture that seems harmless to you may be very troubling to someone else. For example, I’ve been surprised to meet tour guides who don’t like their image shared on the internet (discovered only after the tour, when I mentioned that we have a travel blog and we’d like to shout out their business). I found myself wishing I had asked ahead of time, because many of my photos had the guide’s face in them!

You can avoid this awkward scenario by having a quick and easy conversation so you know where you stand. It doesn’t have to be a big discussion on the meaning of consent; just find a simple way of explaining how big an audience might see this photo if you post it.

For example, I might say: “I write a travel blog and I’d love to share your picture along with a story about how much fun I had staying with your family and learning about Cambodia. Just so you know, my social media is public and thousands of people see it every month, is that OK with you?”

I think it’s important to let people know why you want to share their photo – that you gained something meaningful from your interaction with them, and you’d like to use that to tell others a positive story about their country. Or maybe you’re only planning on sharing a Facebook album with a few family and friends so they can see your trip – adjust what you say accordingly.

We made sure Daniel, the owner of our favorite restaurant in El Salvador, Entre Nubes, knew we wanted to share his photo on our blog and in the hopes it would bring more business his way.

Then practice that sentence a lot! It will feel awkward the first few times, so just do it until it becomes automatic.

(Bonus: The more other people see you doing this, the more it will seem like the norm and more folks will join in!)

But before any of this consent talk, put in some time! Keep in mind that people are not objects. If you want to take a photo of someone, step one should be to engage them in polite conversation.

If you’re taking a tour, introduce yourself to your guide and get to know them a bit before you start snapping selfies with them. If you’re shopping at a street market and want to take a photo of a visually impressive stall, maybe buy a little something before you stick your camera in the shop owner’s face. (I promise you’ll get more interesting and meaningful pictures from this practice, in addition to it being the polite thing to do.)

WHAT IF YOU DIDN’T GET CONSENT?

If you didn’t have the chance to have the conversation or you just plain forgot, I have a couple of solutions for you:

Blur or cover the faces! It’s very simple to obscure people’s faces in your photos app before you post them. This is a solution I use a lot, since I love to take photos on the street that show interesting details about a place (like women carrying baskets of fruit on their heads in Zambia). If a person is recognizable in my photo but I didn’t get a chance to chat with them, I make sure to cover their face before posting it.

You don’t have to post every photo you take. I can’t begin to count the number of pictures I have saved in my phone or computer that make me smile when I come across them – but I’d never put them up on social media. Photos I’ve snapped with patients I bonded with, selfies of throngs of kids following me down the street in Uganda, class pictures of Aaron’s students in Tanzania. They all represent wonderful memories that are just for me. It’s fine to have them, but the whole world doesn’t get to see them.

As always, the litmus test for this is: Would I do the same thing at home? And in this case the answer is yes, I definitely do. We all have photos on our phones that we treasure because they make us laugh, or capture an important moment – but they’re not necessarily images we’d post uncensored for everyone to see.

So go ahead, snap that selfie with the neighborhood kiddos at your homestay and make some friends while you’re at it – but keep those photos to yourself or at least cover up some faces.

PRIVACY: EVERYONE HAS A RIGHT TO IT

Somehow it seems that when we’re traveling, everyone and everything around us feels like part of a tourist display. Locals’ clothes, hairstyles, and behaviors are all so unique and interesting to us that we just can’t help snapping a photo.

But people aren’t tourist attractions. They’re just regular folks trying to live their lives. Every photo reveals something about its subject, and you may not even realize what private details your photo broadcasts to the world.

A perfect example, and a huge pet peeve of mine, is revealing people’s medical information on social media. If everyone at home knows you’re volunteering at a center for kids with HIV and you post a photo of yourself with a group of children, it doesn’t take a genius to figure out they’re all HIV positive – even if you don’t say it outright.

Revealing someone’s HIV status can be devastating. In many places in the world, stigma against the disease is rampant. Being “outed” as HIV positive could mean losing their job, their partner, and being ostracized from their community. And even in places where HIV is better understood, it’s simply not your information to reveal.

We made sure to ask the ladies of Nairobi’s Resilient Women of Kenya tour before we shared their photos. Many of them told us personal stories that they could have preferred to keep private.

Or, imagine you’re frequenting a business that supports women who have escaped abusive relationships – you might want to share a photo along with their inspiring story, but they might be endangered by having their location posted online. Or what if you’re partying at a gay bar, or having dinner in a local’s home, or taking a picture of someone at their job?

It’s important to think critically about what information your photo might be giving away that doesn’t seem private to you.

WHAT ABOUT WHEN YOU’RE IN A PUBLIC PLACE?

Does a right to privacy mean you can’t ever post a picture of another human being without getting their informed consent first? Of course not. If you’re out in public – at a street fair or a concert, for example – then in my opinion photos of the crowd are fair game. As long as you’re not singling someone out, I think most people are aware that if they’re in a public gathering their image might get snapped in a photo of the general scene.

In my opinion, general photos of people in a public place (like this market in Kenya) are fair game.

Another easy solution: In cases where you’re not sure if it’s appropriate to capture someone’s face or you’re not able to have the consent conversation, make an effort to frame your photo so that you capture the backs of people’s heads instead of their faces. (It’s actually super easy and forces you to look at the scene differently, so you might get a better shot anyway!)

I wasn’t able to have a discussion about sharing photos of this prenatal education class in Haiti, but avoiding capturing the womens’ faces made for a more interesting photo anyway.

DON’T ENCOURAGE BAD BEHAVIOR.

As a general rule, don’t be a jerk. But if you can’t help being a jerk, at least don’t display it on social media.

Remember that photos proudly posted and accruing “likes” encourage others to emulate them. So don’t share a photo of yourself doing something that you wouldn’t want everyone else to do.

You may think to yourself: “I’m just one person. It won’t make any difference if I climb over this fence/ride this elephant/pose with this orphan.” But the problem is, you’re not the only one. You’re posting the photo because, it’s safe to assume, something about it looks cool – which tacitly tells everyone who sees it that what you’re doing is a great idea and they should do it, too.

For example: Let’s say you hop out of your car at Yellowstone National Park to approach a bison for a selfie (ignoring the park’s guidelines to stay at least 75 feet away from large animals). You post that photo on Instagram, other people see it and assume that’s an acceptable way of behaving, and then someone ends up like this.

The pursuit of selfies with wildlife has led to a horrifically cruel animal tourism business. Photographs of people volunteering at orphanages in developing countries has created an exploitative voluntourism industry that endangers vulnerable children. You’re NOT just one person – you exist in a broader context, and the photographs you post become part of the ecosystem in which we all live and take our cues for what is appropriate behavior.

I swam with captive dolphins in Mexico because I’d seen plenty of other people share photos like this and therefore assumed it was OK. It’s definitely not OK.

And speaking of volunteering abroad: Even when you’ve done all your research and you know you’re not engaging in unethical behavior, think VERY CAREFULLY about what your photos express (each one’s worth a thousand words, right?).

What power dynamic are you portraying? Are you literally at the center of every photo, or are you moving the spotlight off yourself and onto locals? Are you documenting only the tragic and shocking aspects of your experience, or highlighting beautiful moments and humanizing the folks you work with? (I encourage you to check out @nowhitesaviors on Instagram for more discussion on this.)

Of course, all of this context often can’t be captured in a single image. Which is why we’re fortunate that captions exist!

USE CAPTIONS WISELY

If you follow us on Instagram, then you already know I LOVE a caption. The words you choose to share alongside your photo can make all the difference.

You get to decide what story you’re telling. Your photographs may be the only information that some people access about the place you’re visiting – that’s an awesome power to wield. What aspect of this destination, this community, or this person do you want to focus on?

Do you want to rely on tired clichés and tell a story that’s been told a million times before? Or do you want to use your voice to say something that matters?

A great example is the Barbie Savior Instagram account, which pokes fun at the kind of photos and captions that make me roll my eyes so far back it hurts:

When I’m on a medical mission, I try to take photos and write captions that highlight the incredible work locals are doing, to fight stereotypes that developing countries need foreigners to “save” them. For example: If you’re volunteering abroad, craft a caption that highlights the incredible work that local leaders are doing instead of humble-bragging about how serving the poor has taught you so much.

The same goes for any kind of travel: If you’re visiting a developing country that only appears in news stories about famine and war, tell a story that illustrates the beautiful parts of that place – the aspects most people don’t get to see. Or if you’re traveling on Indigenous land (which is basically everywhere), use that opportunity to pass the microphone to the Native people who live there.

A few questions to ask yourself as you’re drafting a caption: Whose story are you telling? Whose voice are you amplifying, and whose are you ignoring? What biases influence you? What biases does your post support or subvert?

TO GEOTAG OR NOT TO GEOTAG?

OK, so you’ve chosen a mind-blowing photo and crafted a world-changing caption. Now you can just tag the location and click “post”, right? Wait, there’s controversy about that, too?

With over-tourism on the rise and bad behavior threatening some of the worlds’ most beautiful natural wonders, there have been calls for travelers to stop tagging their locations in their photos. If people can’t see the location of that beautiful waterfall, the argument goes, then masses of ignorant tourists won’t flock there to trash it.

But let’s be honest, none of these places are truly secret. If someone wants to find out where your photo was taken, then Google and a bit of persistence will get them there. The only thing that hiding your location does is make the outdoors seem exclusive and unreachable. Which means that groups that have historically lacked access to travel and the great outdoors will have to struggle even harder to enjoy the privileges that many of us take for granted.

Who are we to be the gatekeepers of the outdoors, passing judgment on who’s worthy of going where? (Read this great article for more on that!)

I don’t think that trying to keep the outdoors a secret is the solution to this problem. I think education is.

Remember a minute ago when I told you to use your captions wisely? This is what I’m talking about. If you’re worried about wildflowers being trampled on a beloved hike, include a line reminding folks to stay on marked trails. If you think that extra tourists might trash a little-known beach, encourage visitors to bring a bag and pick up a few pieces of garbage while they’re there. Instead of hoarding your favorite places like they belong only to you, offer others the information needed to enjoy them responsibly.

Or, if the place you’re visiting truly is so secret and fragile that an influx of visitors would destroy it – then why are you posting pictures of it at all?

Want extra credit in the geotagging department? Acknowledge Native land.

As an American, I can only speak intelligently about this in relation to the United States, but it’s true basically everywhere: Public land is Native land. Americans are able to enjoy our National Parks only because Native Americans were moved off of those lands by force. Today, not only do they no longer reside on their ancestral lands and sacred sites, but they also see none of the profits from tourism and often aren’t even mentioned in the parks’ educational materials.

Glacier National Park was Blackfoot land until the tribe was forcibly moved to establish the park. Including a land acknowledgment in our posts is a simple step in the right direction.

So if you’re geotagging your location as “Yellowstone National Park”, why not also mention that you’re on Cheyenne and Apsaalooké land? Our land acknowledgment is as simple as a map pin emoji at the end of each caption pointing out which Native American tribes call this land home. (You can easily find that information using the Native Land website and app.)

AIM FOR PROGRESS, NOT PERFECTION

Nobody’s perfect, least of all us. We don’t expect anyone reading this to be, either. What matters is that you’re open to learning and trying to do better.

What do you think? Do you consider ethical social media use when you’re traveling? Will you start now?

No elephant rides or tiger selfies here - Check out our top 5 examples of ethical animal tourism.